All Nonfiction

- Bullying

- Books

- Academic

- Author Interviews

- Celebrity interviews

- College Articles

- College Essays

- Educator of the Year

- Heroes

- Interviews

- Memoir

- Personal Experience

- Sports

- Travel & Culture

All Opinions

- Bullying

- Current Events / Politics

- Discrimination

- Drugs / Alcohol / Smoking

- Entertainment / Celebrities

- Environment

- Love / Relationships

- Movies / Music / TV

- Pop Culture / Trends

- School / College

- Social Issues / Civics

- Spirituality / Religion

- Sports / Hobbies

All Hot Topics

- Bullying

- Community Service

- Environment

- Health

- Letters to the Editor

- Pride & Prejudice

- What Matters

- Back

Summer Guide

- Program Links

- Program Reviews

- Back

College Guide

- College Links

- College Reviews

- College Essays

- College Articles

- Back

Ninety-Nine

The grade: ninety-nine.

The parents: outraged.

Beet red and tapping dagger-nailed fingers, Mother hurls words. “What happened, Annie, what happened?”

My lips part because I think I might know the answer, but the question’s rhetorical and Mother’s already starting in again.

"You’re disappointing yourself, Annie, and you’re disappointing us.” Her words are brittle, close to a shout but not quite there.

As she trudges on, I touch the glass of water on the table and remember the moment of opening the cool doorknob slowly, unhurried. Of stepping into the house with its dryer-sheet-cleanliness and cool crispness in the air. An easy dimness hung over the room, dressing the chairs in solemn Sunday blues and the walls with dreary black. The quietness felt profound after the unbearable noise of the day, the chatter, the ceaseless ringing in my ear. My keys clattered discordantly against the counter and I nearly jumped at the sound but didn’t because I was too tired for that kind of heady emotion. The day, so fast; the partially turned knob of the sink, dropping water so slowly, achingly. And I watch it. For an hour. It fills halfway before I take it from its metal-walled sanctum and drop ice cubes in slowly, one at a time so that the ring of them against the glass fades from the air in pulsing moments before the next one begins.

Now, the ice cubes have melted, and the glass sweats against my fingertips as I try to call back that moment of calmness.

“Is this what you want in life?” Mother snaps, rubber band words, but I don’t flinch at the impact, not when I can rest assured that she’s more interested in the sound of her own voice than any answer I may give. Besides, I don’t know what I want in life. I know that I am young, and that youth has no place mingling with the careful planning of pantsuits pressed crisply hanging on day-of-the-week coordinated clothes hangers.

My father you can make a study on. The way he stands there, still in his suit from the office with the crinkle in the pants’ knee from sitting all day, in the shirt’s belly from leaning against the crisp glass desk’s edge. He is a rubber man that you can bend and shape into a position to leave there indefinitely, smelling slightly of the whiskey from his flask, not enough to smell on his breath, but just enough to make his eyes vague. Stubble on his chin but only when it catches the light just right because it’s been a while since he cared about keeping himself kempt. Car keys poking through his pockets to the hold-your-breath sports car my mother bought for him to encourage the midlife crisis he’d forgotten to have on his own. He drives that car with his elastic arms placed stiffly on the wheel and his worn shoes barely touching the acceleration at all, going not the speed limit but five miles beneath it, wincing more of a sigh than anything when it chirps heedlessly after he’s locked it up between two other spaces of passive-aggressive jealousy.

Here he stands, looking but not seeing, with his hand on the counter. It looks fat and hairy next to my mother’s veiny, taloned hands. The two of them are side by side, close enough to touch. They don’t. They are twin towers, separate yet just alike.

As I look at their faces, father’s detached, Mother’s reddening, I can lose sensation of the words and see only the strain and flex of the anger on Mother’s face. The stillness was better. I search for the clean smell, but my mother’s maudlin perfume overpowers it. Instead I list what makes up our house methodically until the words are in tune to the dull thump of my heart: front door of chipped wood with its rusting lock flaking bloody chips onto the once pristinely white carpet; coffee table there at a perfect ninety degree angle to the look-but-don’t-touch white leather couch, coffee table with its perfect sheet of glass and only glass, with edges sharp enough to cut you with just a tilt of eyes towards it, with its fragility that drops your voice to a whisper; unopened art books posed like an aloof blonde with a beauty mark above her lip and a fur coat on her needle point shoulders; a vase filled with horrifically perfect red roses, their petals peeled open neatly and a dew drop clinging to the tip of a petal in a perpetual moment of almost. The house is a museum that I tip toe through with bare feet and breath held close, that my mother watches with a hand balancing a crystal wine glass, pretending not to see that dust lies quietly over it all.

Now there is no wine but there’s whiskey fire in her outraged words.

“Do you understand me?” Hand clenching granite so tightly now that her knuckles are white as bone, as the leather of our museum bench.

Silence.

She looks at me; there’s black specks under her eyes because at some point in some hour she’s rubbed at her eyes in vain to ease the pounding in her skull. I close my hand fully over the nervous precipitation on the glass until my knuckles are white too and the cold is sharp enough to burn me back to life.

“Okay,” I say, flat enough for a marble to sit in perfect rest atop it.

Attention shifts then, the camera urged by unspoken words, and we look to my father, and at his indifference. He blinks a startled flap of butterfly wing eyelashes that aren’t getting anywhere as his eyes struggle back into focus, to take in the room, the people, the moment.

And he echoes, “Okay.”

Then they’re back to looking at me, but the weight of their eyes is heavy enough for me to feel the closing of my throat and slow crushing of my chest. I leap from the stool with the energy of spontaneity and trip graceless steps across the room to the door. My water-slick hand smears frantically over the lock until the water’s all gone and I feel only the scrape of dilapidation and the dim fear of stray metal inviting violent disease into my distracted blood stream. It is gone and I am here and the doorknob is still rusting, now rusting with a shimmer of salty-eyed water. And I stare at it. Hear my parents’ voices, both now, blaring words that have lost their meaning. Wait until Mother sighs dramatically, audibly, exasperatedly, and takes her full-to-the-rim wine glass to her room, heedless of the crimson drops that slosh over the lip of the glass to bloodily stain the kitchen floor. Until my father takes off his dust-and-dirt colored suit jacket slowly, one arm at a time, one slow bend of an elbow at a time, one elongated shift of a muscle at a time, until he rests it carefully on the kitchen counter. He stands there and considers for long ticks of some imagined clock in his head before he takes my water glass. Dumps it down the sink. One drop at a time. Empty he leaves it bottom up; empty he leaves the room.

Still I stare because this I know: I want to leave it different than it was before; I want to change something. But the lock is dry now and the lock drops another thin flake of bloody skin to speckle the once-white carpet.

I stand so slowly that my joints crack loudly, angle myself stiffly towards the hallway across from my parent’s tombstone quiet hallway, and take small steps towards my room. There’s a humming in the air and it grates slowly against the shapes that make up the whole, peeling away the artificial gray that covers the soft wood of the dresser, rattling the glass covering a view of our small world within the gates, steadily shaking the three perfectly sharpened number two pencils off of my desk with its stack of orderly papers with my name and the date signed exactly the same way over and over again.

But it stops.

I paint my nails black enough to feel heavy. Fill my mother’s empty wine bottle with my father’s liquor, not bothering to care when the amber stuff splatters messily across the carpet. Take a sip of the stuff. Feel it burn. Sputter it right back out in a flaming spray across my room. Wipe a hand across my mouth. Try again. Find the keys with boneless fingers from the day I put them there, shaky-fingered with the sensation of transparency, red-faced with guilt. I take another sip from my bottle. This one I hold down.

Behind me, doors slam hard enough to rip off layers of rust.

I will leave this house in my father’s fat Porsche. I will drink until this bottle’s all gone. I will drive until there are skid marks somewhere. And when I come back, they will ask me what I have done, and this is what I’ll tell them: this is the transformation of a good girl gone bad.

Similar Articles

JOIN THE DISCUSSION

This article has 0 comments.

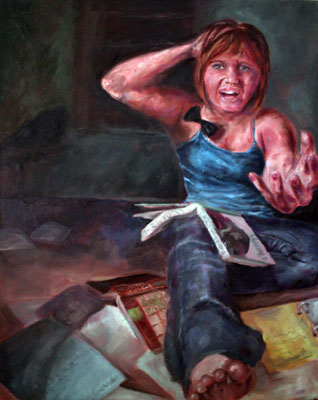

"99" explores the effect of immense academic pressures on the psyche of a girl pushed too far. In a day of standardized tests, class rank, GPA, and plummeting college acceptance rates, you don’t have to look far to find the example of the star student inched over the edge one grade at a time. Students push themselves until they are mechanical, until they view their classmates as insidious enemies on a battle field of class rank, and until their beds are like your mother's aunt's children: rarely visited and strange. While this may have been the inspiration, Annie's story is not just of academic pressures alone: hers is an exploration of the impetus for the zealous drive for perfection more so than the perfection itself.