All Nonfiction

- Bullying

- Books

- Academic

- Author Interviews

- Celebrity interviews

- College Articles

- College Essays

- Educator of the Year

- Heroes

- Interviews

- Memoir

- Personal Experience

- Sports

- Travel & Culture

All Opinions

- Bullying

- Current Events / Politics

- Discrimination

- Drugs / Alcohol / Smoking

- Entertainment / Celebrities

- Environment

- Love / Relationships

- Movies / Music / TV

- Pop Culture / Trends

- School / College

- Social Issues / Civics

- Spirituality / Religion

- Sports / Hobbies

All Hot Topics

- Bullying

- Community Service

- Environment

- Health

- Letters to the Editor

- Pride & Prejudice

- What Matters

- Back

Summer Guide

- Program Links

- Program Reviews

- Back

College Guide

- College Links

- College Reviews

- College Essays

- College Articles

- Back

The Christmas Writer

The smell of books is not really something that you usually notice. Most likely, you never have smelled books regularly, or been surrounded by them enough to notice. I never really thought about the smell of books until I tasted them, until I felt them, until I lived in them and with them. Rohtua Smith knew what books smelled like, but he never stopped to consider it. He had more important things to get done.

At times, Rohtua would pull at his hair wildly, as if he was looking for something. I liked to think of it as searching for a needle in a haystack, but the needle was never there. After the most stressful sessions, some of his hair would stick to his jacket and make him look very silly, but nobody would tell him, because they didn’t want him to become angrier than he already was. The maids would whisper about it as they cleaned his room, but that was only for them to know.

The room where Rohtua worked was very dark. His windows were coated in ash, making the light muddy and gloomy. His desk, the shelves that lined the three non-windowed walls, and the chair in which he sat were all wooden. The wood they were made of seemed to glisten perpetually, even when the murky light faded. It was a sort of mahogany that made you think of stone coated in dried blood. Rohtua seemed to love this wood deeply, but he refused to buy another chair for visitors to sit in. The carpeted floor was a similar maroon to the the rest of the room. No shadow ever seemed to touch it, nor did any light.

Rohtua closely resembled the room where he spent most of his waking hours. His hair was dark and shiny, except when it got matted or ruffled when he ran his fingers through it. His jackets were all maroon and gloomy, and his shoes were black and shineless.

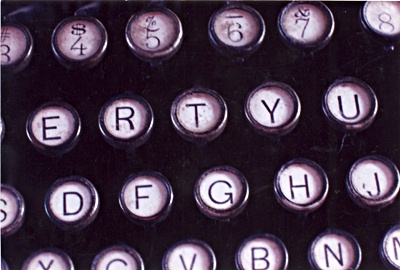

For a while he liked writing with his hand and a pen, but the editors got tired of having secretaries copy down his work. When he finally switched to a typewriter, I thought that it would be too loud, but it made little noise. I think that it was so unusually quiet because Rohtua could never think of anything to write about.

It all began when Rohtua was writing a Christmas story. It didn’t have to rhyme, the editors told him, but it had to be cheerful and touching, and that was it. No other prompting, only a deadline. Rohtua kept asking if there was anything else that he needed to include, desperately trying to make some sense of the assignment, but there was no reply. The editors left the office, and Rohtua began to think.

After thinking for a good long while, Rohtua got up. He stood for another good long while, and after that, he paced about the room. Sometimes he would pick up a book and read a few words. Then, he would either read those words again, or thumb through the rest of the book and put it back down. It never seemed to be the right book, but after a while, he had looked through all of the books in the room.

He sat back down and began to write. He struck the keys with vigor, only pausing every minute or so to angrily rip a paper from the jaws of his typewriter and throw it against the thick windows, where they collected, some sitting on the deep window sills, others falling to the floor. Rohtua was not the type of person to get too angry, but a haze of rage started to seep from every movement he made. His typing became more erratic, causing him to waste more papers. The sills were now all full, and the tide of waste started encroaching on his chair and the book shelves that shored his desk.

Still further his rage increased. The paper balls were thrown harder and faster. Rohtua was no longer writing. I could not discern what he even was trying to accomplish. He was crumpling up the paper without even attempting to write anything on it. All at once, he seized his typewriter and hurled it against the window. It made a loud thud, but did not break. As it fell to the floor, the shelves that I was sitting on shook.

“GOD DAMN IT!”

There was no man anymore. Rohtua lay on the floor, crumpled with all of his wasted papers. His eyes were open wide, and he shivered. I had never seen a human act this way. When an animal was caught and dying, it often would lay like that. Rohtua now lay, trapped by his own mind, prey of nothing.

“What seems to be the matter?”

A maid cautiously opened the door, and seeing Rohtua, ran over to him and knelt.

“Mr. Smith? Mr. Smith! Are you there? Please answer me. ANSWER ME!” she cried out. “I KNOW YOU’RE THERE!”

The maid broke down sobbing. It was an unusual sight. The paper covering the maroon carpet resembled a heavy blanket of snow, just like the one that lay on the ground outside. Another maid came in and knelt over the first maid, trying to calm her. Some of the editors poked their heads through the door. They seemed concerned not with the health of the man that lay before them, but the story that he had been assigned to write.

“What about the story?” one of them whispered. “How will we have Christmas without a story?”

“Can we recycle the one from last year? Nobody will notice, right?” noted a second.

The first nodded, and called to a secretary to fetch the story for him. An ambulance came, and the room was flooded with medical personnel. All of the commotion made me extremely nervous, so I ducked out of sight and returned to my nest to sleep.

The next day, Rohtua wasn’t there. The office lay empty for most of the day. Towards the later hours, when the sky was getting dark (as it does during the winter), the maids came in to make their daily rounds. I could immediately tell that there was a certain tension in their conversation, in their movements. As close as I could get without being seen, I listened.

“How is he doing?”

“Mary went over to the hospital to see him, but she hasn’t come back.”

“I hope he’s alright.”

“I think we all do.”

The second maid leaned closer to the first.

“Except for maybe the editors.”

The first one straightened up and glared at the other.

“And what exactly makes you think that?”

“Whenever they talk about him, they always sound like they want him replaced.”

The first maid still looked very annoyed.

“Well, do you agree with them?”

“Heavens no! Rohtua is the only sane person here!”

One of the editors walked by, and the maids quickly went back to their cleaning.

A long time seemed to pass until Rohtua returned. When he did, there was much fanfare behind his back, but he immediately returned to his old routine. At first, the excitement that filled the building was distracting. When things returned to normal at last, I could see that Rohtua had changed.

He always smiled. He had never smiled much before, but at least you could tell when he was happy. Now, there was no emotion. An air of empty happiness followed him, not only in the way that he worked, but in the way that people looked at him and whispered behind his back. His way of writing was much less emotional as well. He used to get up and walk around as he worked, talking to himself. Now, he sat in his chair, motionless except for his fingers. If he made a typing error, he wouldn’t take the paper out and ball it up. He simply pulled it out gently and let it fall to the floor, and then he would start again.

Another month passed. One night, as the maids were cleaning, I once again leaned in and listened. For a while, neither one spoke. Then, the maid that had first found Rohtua spoke.

“I can’t believe it.”

“What’s the matter?” The maid that had held her replied.

“Rohtua isn’t the same.”

The other maid didn’t reply for a while. When she finally did, there was only a hint of sorrow in her voice.

“The editors are talking.”

“What about?” The first maid seemed worried.

“You know… Rohtua. He’s getting a little old. He can’t think straight. His writing is no longer what it used to be. It’s lost its emotion.”

“Nonsense!” I could tell the first maid was nervous. “He’s the sanest person here! He always has been, and always will be. No more talk of this.”

More silence. It was almost forever before the second maid worked up the courage to speak. She seemed to say what everyone was thinking.

“Rohtua isn’t going to make it.”

It was as if all of the excess air had been let out of the room, and it was easier to breathe. The first maid sat down in Rohtua’s chair and hung her head in her hands. She didn’t appear to be crying, or at least she cried silently. The second maid looked at her for a long while, then came over and knelt next to her.

“There’s nothing we can do. I wish there was, but the editors rule, like they always say themselves. We can only hope and wait.”

The sitting maid removed her head from her hands with all of her might and stared straight into the eyes of the other. Then, like a child returning from war, they embraced each other. For a good long while they stayed there, not moving, not thinking. The room darkened in the evening light. At last they stood up, finished their cleaning silently, and left.

???

It was Christmas again. The editors were nowhere to be seen. They had shut all of their doors and only spoke through series of secretaries. There was no jolly spirit in the air, as there had been a year before. In its place was a pall of suspicion. Nobody wanted to let Rohtua go, not even the editors. But the paper had been losing money, and whispers had been circulating among the maids that it would soon be time to find somebody new.

Rohtua was once again given a Christmas story assignment. There had been some controversy, because the editors were worried that if they had to use the same story three years in a row, people would get suspicious. Others thought that it might be dangerous for his condition to put him in the same place that had made him the way he now was. In the end it was settled that, if he failed again, they could use the Christmas story from four years ago instead. And so, a secretary delivered the message to Rohtua, and then to the maids.

Rohtua read over the paper. He seemed to be puzzled for a good long while. He sat in that way that he had done for so long, thinking. But there was no longer a passive smile on his face. He furrowed his brow. He tapped his finger on his desk. These behaviors were so strange to me that I moved to a higher shelf for a better look.

Memories came rushing back to me of how Rohtua had once been. Quizzical, frustrating, intellectual, and above all else, alive. How long it had been since I had seen him think so hard and so deeply about something, I could not tell.

At last Rohtua rose from his chair. So much sitting in the past year had worsened his condition, but he managed to hobble around in a slow circle. He started picking up books and thumbing carefully through them, reading paragraphs or sentences or single letters. Every time he got tired of a book, he simply placed it back on its proper shelf. He made his rounds so slowly that I had no time to think when he finally came to the shelf that I sat on.

The book that concealed me slowly slid off of the shelf. I was blinded by the still mud-like light that poured through the windows. When I could finally see again, I was staring straight into the eyes of the man that I once knew, Rohtua Smith. His eyes sparkled and a smile spread across his face until he looked like a madman. He chuckled deeply to himself.

“How funny, I’ve just thought of an idea for a story. It’s about a little rat that lives in a house with a family and secretly celebrates Christmas while they are sleeping on Christmas eve. Do you like that idea?”

Never in my life has I wished so badly that I could speak or at least nod my head. I guess that he could tell what I was thinking, because he replaced the book on its shelf and nodded to himself.

“Yes, that sounds like a wonderful idea.”

Similar Articles

JOIN THE DISCUSSION

This article has 0 comments.